Clara Vlessing peeks into TLP’s De la lumière à l’ombre to explore what comics can do.

Clara is MSCA SoE FWO postdoctoral researcher at Ghent University.

Comics are an unusual medium: fast to read; slow to make. They’re dependent on their readers to interpret still images as dynamic movements, to turn clouds into thoughts, curly lines into smells or simplified icons into fleshed-out people. In the past forty or so years, comics have become a popular way to share interpretations of historical events: from the struggle for civil rights narrated in Lewis, Aydin and Powell’s March trilogy (2013-2016) to 2009’s Logicomix, which considers Bertrand Russell’s work on the foundational quest in mathematics, via now canonical examples like Satrapi’s personal account of coming of age during the Islamic Revolution in Persepolis (2000-2003) or Sacco’s investigative journalism in Palestine (2000) and Footnotes in Gaza (2009) – to name a few. Academic and less-academic analyses alike are replete with claims about what this irreverent medium can bring to our understandings of pasts that are unsettled, disputed or inflammatory.

“Cartoons have an immediacy that prose can’t have,” writes Art Spiegelman, whose late twentieth-century history of his father’s survival of the Holocaust, Maus, is frequently cited as an instigator of a mainstream appetite for ‘serious’ stories in comic form – often called ‘graphic novels’. Here I stick to the broader term ‘comics’, following scholars such as Roger Sabin who consider ‘graphic novel’ as a marketing term rather than a descriptor of a medium, and in keeping with Spiegelman’s own discomfort with having his work characterised as novelistic.

Historic comics undercut any idea of a monolithic ‘truth’ and highlight the extent to which the versions of the past that reach us are the product of repeated retelling.

In creating immediacy, comics take a two-pronged approach. They can make meaning faster and more economically than media forms that are solely text- or image-based, moving between plots, locations, historical periods, perspectives and moods with ease and speed. They appeal to the reader both as works of literature and works of art.

On top of their immediacy, comics are particularly good at accommodating narrative diversity or multiplicity. As what comic scholar Hillary Chute has called, a “conspicuously artificial” medium, comics tend to steer clear of the associations with truth, objectivity and realism that adhere to media like documentary film or photography. Instead, they often draw attention to the process of crafting a story, using stylised drawings, bright colours or monochrome outlines to creatively replicate and reinterpret diverse events and artefacts.

The medium’s inherent playfulness means that comics are rarely rigid or dogmatic but self-conscious, layered and equivocal, making ideas available to new audiences or providing a change in perspective about the past. Historic comics undercut any idea of a monolithic ‘truth’ and highlight the extent to which the versions of the past that reach us are the product of repeated retelling and remaking by different people and across different media.

In this vein, Spiegelman identifies the act of creating a comic as one of selection between different truths: “It’s about choices being made,” he writes, “of finding what one can tell, and what one can reveal, and what one can reveal beyond what one knows one is revealing”. His words point to a tension between material availability and creative intention that is at the heart of the historical comic, in which images and words work in tandem to tell and show obscured or unexpected pasts. As works of archiving and of imagination, historic comics ask questions about what sort of pasts are available. What are the sources or explanations for these pasts? How are they best represented? And for what audiences?

Introducing De la lumière à l’ombre

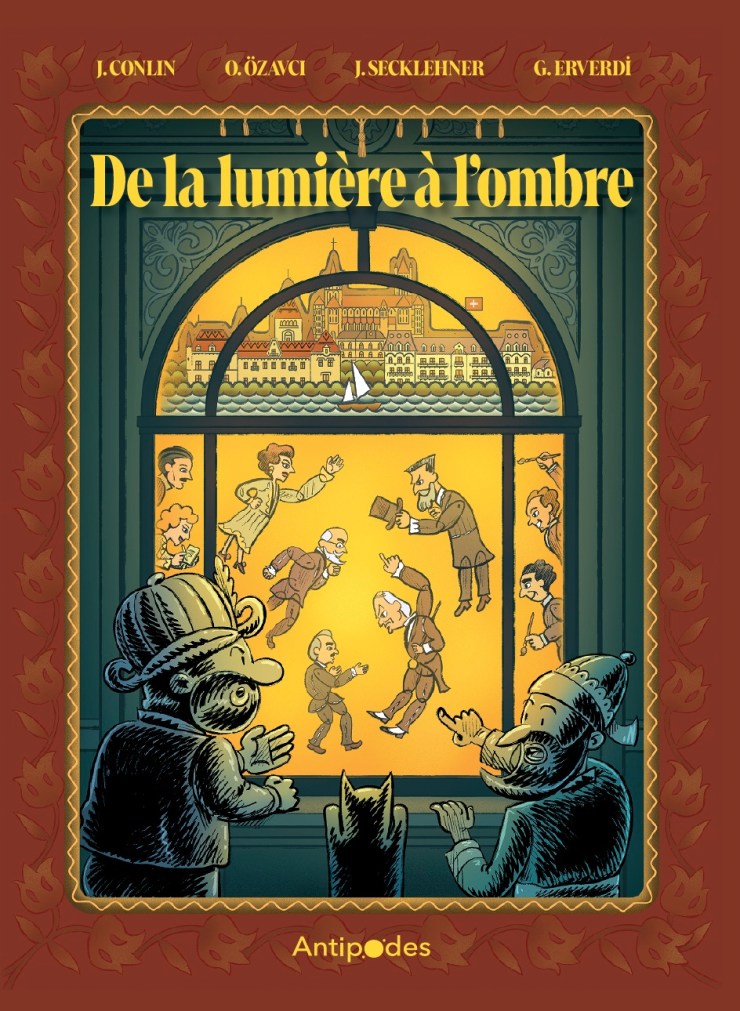

Within the context of TLP, the comic has an evidently pedagogical intention: it is part of an endeavour to share the story of Lausanne with new publics with humour and inventiveness. It was produced by the TLP’s founders Ozan Ozavci and Jonathan Conlin, alongside art historian Julia Secklehner, who first met in June 2022 to write a script for the story before enlisting the help of artist Gökçe Erverdi, who drew the comic. The comic is intended for high school-aged readers in diverse contexts and its creation is the outcome of an active process of decision-making about how best to widely communicate historical findings. Currently available in French and with forthcoming editions in English, Greek and Turkish, De la lumière à l’ombre seeks a transnational audience, moving smoothly across borders that the Treaty itself entrenched.

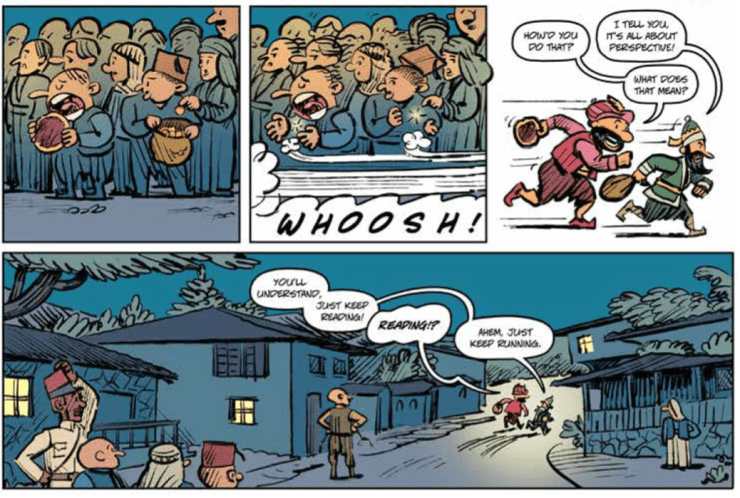

The comic tells the tale of Hacivat and Karagöz, a pair of troublesome shadow puppets from the town of Erzin, who escape their puppeteer – becoming real by, in the words of the comic, “changing their perspective” – and head off to Lausanne to seek their fortune. Along the way they meet a cat called Schubert, who has been separated from his forcibly-migrated family, as well as a host of prominent figures whose presence at the treaty negotiations is well-documented. These include Turkish negotiator and Atatürk’s right-hand man İsmet İnönü, British representative George Nathaniel Curzon, Bulgarian diplomat Nadejda Stancioff and journalists Claire Sheridan and Ernest Hemingway.

Produced alongside learning materials, blogs and other carriers of collective memory, De la lumière à l’ombre advances TLP’s broader aim to make the events leading up to the Treaty more visible.

Through a dynamic series of incidents and plot twists, described by one review as ‘dizzying’, our heroes find themselves present at many of the events of the Lausanne Peace Conference. These range from intimate negotiating tables to boat trips to luxurious masked balls. In the comic book’s final pages, as the Treaty is signed, Hacivat and Karagöz return to their humble origins with a new story for their puppeteer – and newfound negotiating skills.

De la lumière à l’ombre is unlike other types of learning resources and sources of information about Lausanne. It takes advantage of the form and associations of the comic form to bring levity and nuance to the story of the Treaty through its use of narrative devices, motifs and verbal-visual metaphors. Above all, it presents history as a story.

Puppetry in De la lumière à l’ombre

Using the inherent playfulness of the medium, the comic includes a recurrent motif of puppets and puppetry and draws attention to the theatrical aspects of the Lausanne Conference. Performing on the part of powerful states, businesses or newspapers the characters at the conference are, like puppets, representative. They may appear to act independently but their actions are guided by external forces.

The most obvious example of this motif is the inclusion and characterisation of Hacivat and Karagöz themselves. These characters are derived from stock figures in traditional shadow plays popularised during the Ottoman era across Turkey, Greece and the Balkans and have well-established personalities. Hacivat is clever and scheming, Karagöz bumbling and impulsive. Their presence brings performance, play and artifice to the forefront of the plot.

In particular, the notion that through a ‘change in perspective’ the pretend can become real reframes the relationship between subjective and objective understandings of the past: truth or ‘reality’ becomes a question of positioning; the reader must be open to different interpretations of historical events.

With its now-human shadow puppet heroes at the heart of the story, De la lumière à l’ombre goes on to play with the effects and outcomes of puppetry throughout its depiction of the Lausanne Conference. Delegates are often referred to as puppets and Karagöz plays with puppet-sized versions of İsmet, Curzon and the French spokesman Camille Barrère in an attempt to reconstruct a meeting at which he has fallen asleep.

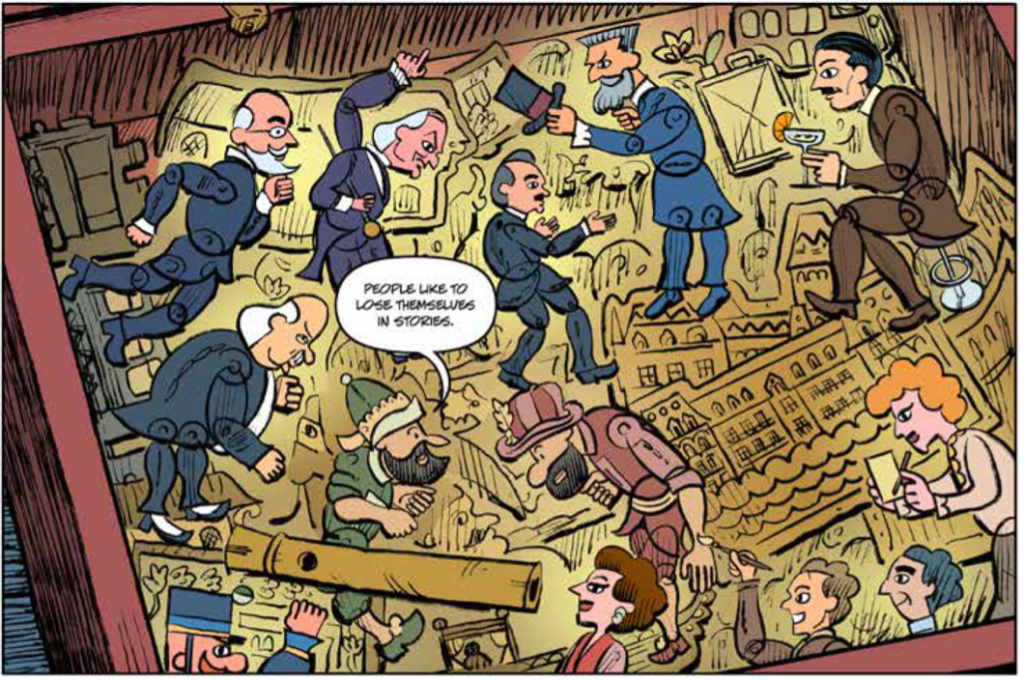

As the story comes to a close and Karagöz and Hacivat return home, becoming actual puppets once more, a large panel shows a bird’s eye view of the puppeteer’s box, sitting on the floor. Within it lie various of the characters we have previously encountered now also in puppet form; the manufactured joints between their limbs and bodies are showing and their profiles are permanently turned to the side.

Implicit in this frame are several suggestions about puppetry in relation to the comic’s historical subject. First and foremost, the panel points out that these characters have been puppets in the story we have just read; an implication that once more draws attention to the artifice of the comic’s creation and the choices made about what stories we tell and how. But this apotheosis of the motif also underlines the characterisation of participants at the Lausanne Conference as proxies for more powerful entities; their strings pulled by unseen puppeteers.

This is not to say that these participants have no agency – if the events of De la lumière à l’ombre show us anything it is the capacity of ‘puppets’ to make trouble – but it is to insist, as the comic frequently, does, that all is not as it seems. The puppets’ agency is partial and mediated; their puppeteers are hidden. International politics are represented as a performance with numerous puppets and numerous puppeteers. The relationship between the intentions of the puppeteers, the actions of the puppets and the outcomes of those actions is complex and unpredictable.

The version of Lausanne that emerges involves the constant interplay (and play is important here) of events across different scales. The feuding nation states may control the puppets, but the behaviour of the puppets also has an effect on the states.

The absence of any direct explanation of this motif keeps things subtle, avoiding didacticism or stereotype. The version of Lausanne that emerges involves the constant interplay (and play is important here) of events across different scales. The feuding nation states may control the puppets, but the behaviour of the puppets also has an effect on the states: their performances on the stage of the Lausanne Conference have significant consequences for the inhabitants of those states.

Nowhere are the consequences of this puppetry more apparent than in the bittersweet plotline of Schubert the cat. His story shows the impact of the Treaty on the lives of people with little agency. Brought finally to Greece, where his family have been moved, he suffers a brief run-in with some local alley cats before he is reunited with the little girl who lost him.

The episode is heartwarming, the reunion hard-earned, but at the same time it points to the damaging outcomes of the forced migration Schubert’s family have suffered. They may now have their cat, but they are also in a new and hostile environment, far from home. The cartooning allows the narrative to move quickly between moods and locales. The incorporation of this plotline undercuts some of the frivolity of the ‘puppets’’ performance to demonstrate the impact of the Treaty on ordinary people’s lives.

Reconstructing the Lausanne moment

De la lumière à l’ombre utilises the comic form to interrogate a tension between idea and outcome, treaty and practice, puppet and puppeteer. Through a give and take between fact and fiction it draws the reader’s attention to the construction of the comic and the construction of history. The comic has a proximate relationship to its historical sources. It takes content and features from older cultural artefacts, using images and texts from the time of the Treaty, and ‘remediates’ them to create something new.

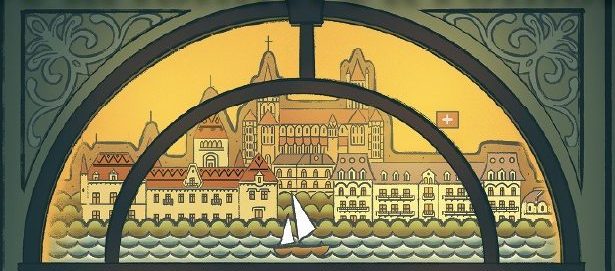

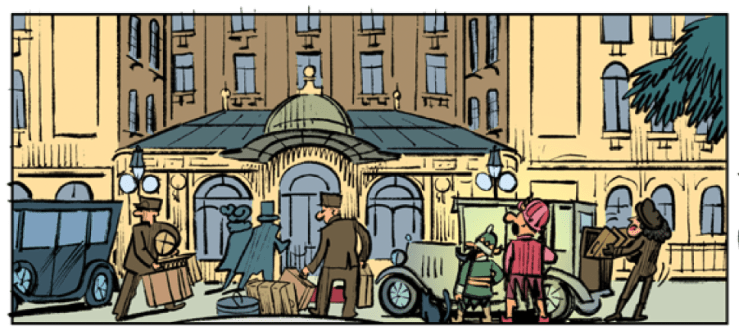

Drawings of the hotels and verdant Swiss hills have a clear correspondence with photographs of Lausanne in 1922-23; newspaper headlines and telegrams appear in the style of the time; dialogue echoes the reportage of those who were at the conference. “What is peace?” exclaims one character, breaking out of his frame to repeat words from Hemingway’s poem about the conference, a mantra that TLP has returned to often.

The comic’s embedding in historical sources is at its most acute in relation to the its reinterpretation of caricatures by Emery Kelèn and Alois Derso. The artists’ album of comical drawings Guignol à Lausanne (1922), renders the people and events of Lausanne, heavily informs the comic’s visual style. Look for instance at the two images below of Curzon and İsmet dancing at the masked ball, the first from Kelèn and Derso’s collection and the second from De la lumière à l’ombre. With the exception of a few details they are identical. Such resemblances are the result of an active choice to ‘reveal’, in Spiegelman’s sense, the Lausanne of Guignol à Lausanne.

Underlining their important role at the conference, Kelèn and Derso themselves also appear as characters in the comic. And the comic’s creators have spoken about their belief that the Hungarian duo’s work translates complex topics in a “diplomatic” way, maintaining a sense of levity rather than hardening political stereotypes – in much the same way as the comic seeks to do.

This remediation celebrates and gives a new platform to the caricaturists’ work. The reinterpretation of their images also has the important effect of placing the comic book within a satirical tradition that reaches back to the Lausanne moment itself. With a few brush strokes, Erverdi sanctions Kelèn and Derso’s interpretations of the conference and creates an undeniable connection between the twenty-first century book and the long-passed events it describes.

Produced alongside learning materials, blogs and other carriers of collective memory, De la lumière à l’ombre advances TLP’s broader aim to make the events leading up to the Treaty more visible. It evokes questions about the lives of the famous figures who are represented in its pages. With a nebulous relationship to historical fact, wherein we must deduce what is fictional (like the puppets who come to life) and what is not (like the historic characters included in the story), readers are inspired to turn to external educational materials in order to separate imagination from reality and make connections between the Treaty and other historic events.

Fitting within a tradition of historic comic books that are neither entirely celebratory nor critical about the pasts they represent, the comic book uses the powerful associations of its medium to reveal the intrigue, the surrealistic qualities, the multiple perspectives and weighty consequences of the Treaty of Lausanne.